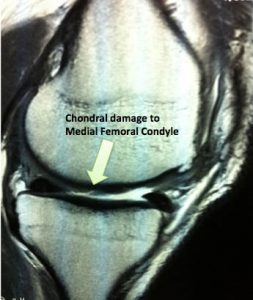

Chondral Grafting in the knee

Articular cartilage injuries in the knee are common and unfortunately the cartilage does not heal or regenerate. They are usually from twisting injuries during sport or work which cause a shearing or impact injury to the knee. Patients complain of swelling, pain or locking in the knee which is worse with activity and does not respond to the usual treatments such as NSAIDS or physiotherapy. These injuries tend to progress and result in degenerative arthritis of the knee. Articular cartilage injury is a common finding at arthroscopy but only about 5% of patients are suitable for some form of chondral grafting.

Injuries that are appropriate for treatment are full-thickness lesions more than 2 cm2 in size in a patient <40 years of age.

Some patients who have isolated chondral lesions (and radiographic arthritis) are still able to live their lives with very few symptoms and some are even able to play regular impact loading sports. Progression of the chondral lesion may depend on it’s size and location, the status of the underlying bone, the presence of arthritis; and patient factors such as age, limb alignment, joint stability and body mass index.

Chondral grafting should only be considered if patients have ongoing symptoms after their initial arthroscopy. It should not be performed as a ‘preventive’ measure.

Articular cartilage lacks a direct vascular supply and nutrients are therefore delivered via the synovial fluid. Diffusion of this fluid through the cartilage requires an intact solid matrix of cells and three main techniques have been developed to ‘restore’ cartilage to the damaged area.

These are 1. Microfracture 2. OAT and 3. ACI.

- Microfracture is the first-line treatment option for full-thickness articular cartilage defects because it is minimally invasive, technicaly easy, has limited surgical morbidity and is low cost. The lesion is débrided, the zone of calcified cartilage is removed and cortical penetration is achieved with an awl, causing medullary bleeding and clot formation. The literature shows clear improvement in knee function at 24 months but inconclusive durability beyond the 2 year mark. There is some evidence that MACI (see below) performed on an area that has been treated with microfracture does not work as well.

- OAT or mosaicplasty involves harvesting viable, structurally intact cartilage and bone plugs from a “less valuable” portion of the knee joint and transplanting that material to the site of symptomatic cartilage injury. Rapid healing and incorporation of the bone plug occurs and the articular gaps fill with fibrous tissue. There are many problems with this technique including: creating symptoms in another part of the knee, thin articular cartilage is used to replace thick cartilage; and the fact that relatively flat cartilage is usually placed on a very rounded surface.

- ACI involves the harvest of chondrocytes in an initial arthroscopic biopsy procedure. This takes far less material than that required for OATS. The specimen is transported to a laboratory, where it is processed and seeded onto a membrane. The ‘graft’ of viable chondrocytes is then implanted on the prepared defect surface in a second open procedure. The recovery phase includes a period of restricted weight bearing and use of a continuous passive motion device. The new cartilage that forms contains components of normal hyaline cartilage with similar morphology. ACI has yielded good to excellent results at 7 years of follow up.

- To watch a video animation of cartilage grafting click here

Generally speaking younger, more active patients have better outcomes in all of these groups. Larger lesions seem to fare better with ACI and OATS than with microfracture but no correlation is seen between the histologic appearance of the repair cartilage and the clinical outcome. Several studies have shown that about 75% of patients have less pain after any of these procedures with a low failure rate. The literature does not show a clear outcome benefit for either ACI or OAT over microfracture so microfracture should be considered the first line therapy given its ease (one-stage procedure) and affordability relative to ACI.

Rehabilitation following ANY articular cartilage repair procedure is long and demanding. This varies with the size and location of the lesion as well as anything else that was required at the operation such as a high tibial osteotomy. It is hoped that in the future mesenchymal stem cells will be available for Cartilage Regeneration but currently only the techniques listed in this article are available.